Part 2 of 8 from the series by Christina Lopinski

„Close the window“. Lucy shakes her head, Cecil closes the window of the van from the inside. Dust swirls through the air, mixing with scraps of Arabic words, children scream. “They have to build a line,” the French woman shouts, her voice drowning. No line, no diapers, we say in Turkish. One of the men shouts, we are bouncers, in a field, somewhere in Izmir, pushing the women into a line. “For your own security,” I say carefully. A black-haired boy looks at me with wide eyes and smiles. He catches my uncertainty, I smile back, then Cecil opens the window and we can continue handing out diapers. I stand to the right of the van with my arms outstretched, turning away the women who try to push past the line. A young woman, younger than me, has tears in her eyes, a torrent of Arabic words comes out of her mouth, she holds her infant in front of my face because the language of compassion is universal. Pity is no help, I’ve learned, so I shake my head and point my finger at the end of the line. We have enough diapers for everyone, I want to say, the language barrier is too great, I try to promise her with my eyes that if need be, I will personally make sure her children are taken care of.

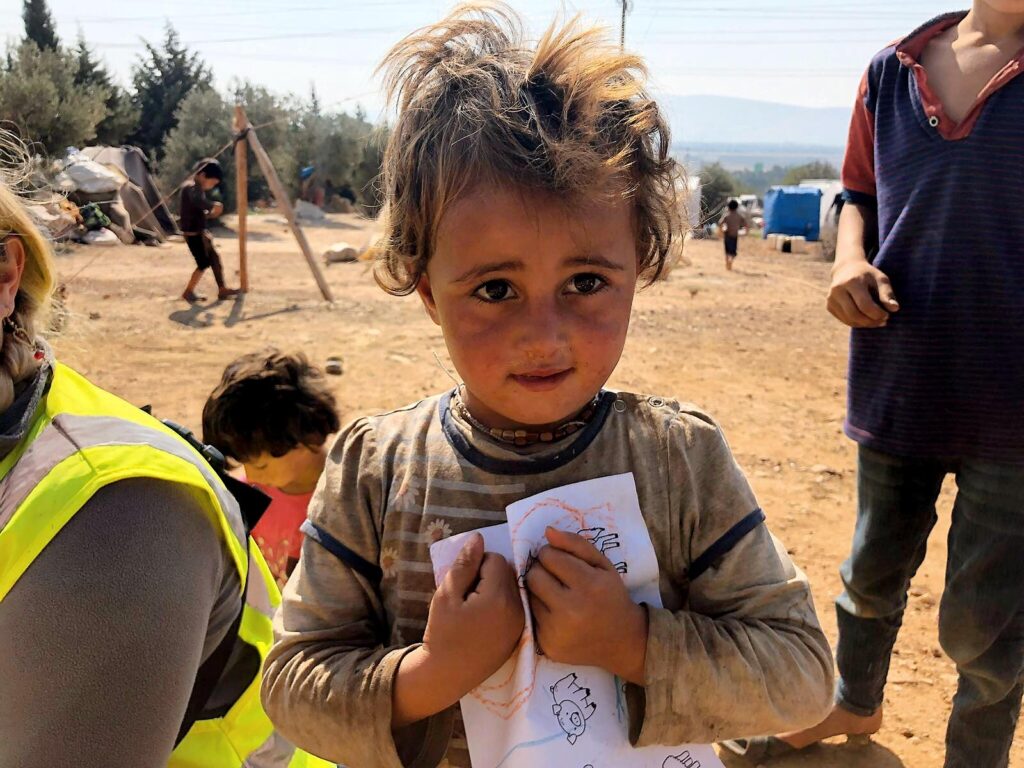

Another clump of women is forming in front of me. Mothers squeeze babies into their eldest daughters’ arms so they can get their turn faster. Children hang from the dress tails of young girls, a few are naked. It’s a concert of screams, as if the little ones sense we’re from another world, as if they want to tell us how much more they need than diapers. It’s all in your head, says Nina. The kids don’t know any different. The black-haired boy is still standing next to me. His skinny body is touching mine, he’s leaning against my legs, he’s four at the most. I watch his mop of hair as I watch the diaper fight. Instinctively, I put my hand on his shoulder. Later I learn that his name is Muhamed.

“Pity is no help, I’ve learned.”

We are in one of the many camps around Izmir, known from the media as Tent City. We have an official permit to supply unofficial camps. This is crazy, Nina says as we drive south in the van. I nod. A hundred families are waiting for us. Later I will understand that a hundred Syrian families are a counterpart to 300 Western European ones. There are up to ten children for every woman, although not a single one can be properly cared for. At a gas station a few kilometers from the camp, we put on our high-visibility vests. We meet three more helpers who have loaded stoves on a truck. “Winter is coming,” I’ve been hearing a little too often these days. Ali briefs us. No promises. We nod. The stoves are distributed first, then diapers, baby powder and hygiene items, clothes and toys last. Nina and I are responsible for the children, while the adults get the things they need. We came up with a sports program, brought a giant puzzle carpet, hula hoops, a kids’ tunnel, balls and pictures to color. In two hours, we’ll be out of tunnels and almost out of crayons. I only now understand the value of toys when you’ve never seen any.

“I only now understand the value of toys when you’ve never seen any before.”

“You have to motivate the kids to come along,” Nina calls out to me. I can’t. I am overwhelmed by the situation and have fears of contact because I have been thrown into a world that is the superlative of awful and exceeds every imagination to such an extent that I do not know how to navigate it. I am trapped in my awkwardness. We drove inland by car, past construction ruins, rubble and debris, until we were greeted by street dogs at camp. Our van parked on the edge and was quickly surrounded by people. Demographic change seems to be happening the other way around here. I don’t see any old people. I look around and try to grasp the situation spatially. Between bushes, on a dusty, stony ground, white tarpaulins, fastened to branches, rise up into the air. You can’t stand under it. I don’t mean to be rude, I hate onlookers. You don’t just walk into other people’s houses at home. Although privacy is a foreign word here, I want to be respectful of people’s private nothing.

The few canvas shelters that give me a glimpse inside re-personalize sparseness. There are colorful rugs on the floor, cooking pots are in the room, blankets are on the floor, there is no furniture, where would this furniture come from? The tarpaulins flutter in the wind. It’s not a problem yet, it’s still warm. When it rains and gets cold, it looks different. Where do people go to the bathroom, I ask Nina as we walk across the nearby field. She points to the floor and I almost step into a pile of feces.

I’m almost knocked over by the women carrying their diaper haul into the tent. A little girl strokes my bracelets, then yanks on them, my favorite bracelet breaks. “Come,” I say, wanting to take her by the hand, my sports program waiting, she’s disappeared behind her mother’s long skirt. Or is it the sister? Girls become women before they could be girls. Children are mothers, everything is so shifted here. Pity is no help, I hear Ali say, and I get the colorful puzzle rug out of the van.

“Girls become women before they could be girls. Children are mothers, everything is so shifted here.”

I fight my way to Nina, past hundreds of children’s hands reaching for me and the carpet. Nina does jumping jacks and sit-ups, the kids who can already stand stand in a circle around her, most of them stare at us as if we were from another planet, we are from another planet, some join in anyway. I spread out the carpet, want to do a puzzle with the kids, it’s impossible because they all pounce on the pieces. “Stop,” I screech, afraid the kids will crush each other. No one hears me. I feel children’s hands in my hair, on my vest, on my bracelets. “Stop,” I shout again, Lucy screams in Turkish, slowly the tangle of children loosens. I think of my time as an exercise instructor in the gymnastics club, of the children’s disinterest in sports equipment because they already own everything: Trampolines in the backyard, and stilts and diabolos and everything ToysRus has to offer. Materialism is redefined by its contrast. And I can hardly suppress my anger. How can it be that our children wallow in materialistic children’s toy heaven and are numb to stuff, and those children’s toys are empty diaper wrappers of their own children?

I’m so angry as I get the tunnel out of the van. I want to try one more time. I want to give the kids a chance to experience crawling through a tunnel, I crawled through entire tunnel cities as a kid, in my parents’ backyard. It doesn’t work. The tunnel breaks the moment it touches the ground. The children can’t get behind each other, the strongest crawl through the tunnel a few times until it is completely broken, the small and timid sit in the dirt and cry. Nina gets paper and pens. We printed out pictures of animals and brought pens to hand out. I take a deep breath and start with the littlest ones. Everyone wants paper. They all draw, hold their pictures in front of my face, the older ones write their names on the back, want me to draw hearts on them. We paint for an eternity, or so it seems to me. The kids are very thorough, with their one pen that barely paints, or is so dull that their black fingernails are used as paint. The girl next to me is named Yara. She points to the purple horse, at, she says, grinning. Harika, I say, stroking her back. Her T-shirt is dirty, the way all kids wear stained, dirty clothes. The mothers and fathers stand in a circle around us. Nereden geliyorsun, says a man sitting in the tent behind me. Where did you come from? Almanya. A young guy comes to me, selfie? I nod before I can think. Before I can think I see myself on his smartphone screen, click, click, click. Almanya, you’ve got enough food and drink there, right? There you have clothes and medicine and houses with roofs, there you have a future. Or. OR? I see it in the man’s eyes, pointing to two men, presumably his sons, who says names and nods at me. I shake my head and look in embarrassment at the purple horse of Yara. I want to take you all with me, but I can’t. No promises, I hear Ali say. Then we need to collect the pens and go. I feel a child’s body against my leg. A little boy presses a picture into my hand. Muhamed, he says. I draw a heart on the back of his paper and trade it for the pen, which he reluctantly returns to me. I want to apologize, to all these people I want to apologize.

“I want to apologize, to all these people I want to apologize. That I have a future. And they don’t.”

It’s not about the pen that Muhamed doesn’t get to keep. I am German, and you are not. And I can’t help it, and neither can you. I want to apologize for that as I say goodbye to Muhamed. That I have a future. And she doesn’t.

About the author:

Christina Lopinski was a volunteer for STELP in the IMECE village in Cesme/Turkey from October to December 2019. The 24-year-old has lived in Berlin for a long time and during that time wrote for the Berliner Abendblatt, the B.Z. and the Wiesbadener Kurier. She currently works for the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung.