Part 3 of 8 from the series by Christina Lopinski

“Broken,” Cam calls out as he hands me the 10-kilo bulgursack. I pass it to Nina, carefully, as the orange lentils fall out of the giant bag onto the dusty department store floor. My arms are tired. My arms are so tired, they threaten to break through like matchsticks with each bag I pass. It’s Monday, it’s dark, the wind is cold. We’ve formed a chain, between the truck and the department store, singing in Turkish and German and French and English, trying not to focus on our aching body parts. Cam and Josh are now part of the big us, part of our family, for this week. The two men from Khalsa Aid, an NGO from England, arrive with a huge shipment of food that we have to unpack and will distribute over the next few days. I’m all excited as Rashid opens the truck doors. A canned food land of milk and oil, flour and sugar, I’ve never seen so much rice and lentils in one place. Our truck is a supermarket. I think of all the people who can get their fill of it, and a warm feeling flows through my body.

“Come on,” Rashid shouts as he sits on hundreds of milk pallets, “let’s go.” We still throw the first 200 packs of baby diapers at each other, joking about unpaid gym memberships as we squat lower than we need to with the flour, “sugar-squat,” Ezgi says, laughing. After 300 liters of oil, the laughter quiets, we are tired, the truck is not even half empty. There are too few of us to take turns, the truck driver wants to go home, we want to go to bed, “I can’t take it anymore,” Carmen moans, we all can’t take it anymore, Carmen. I’m so exhausted and angry, I can’t shower later, and I have to sleep in a container. We have no more room in the warehouse. This isn’t about you, the 20-pound bag of rice says to me as it threatens to slip from my fingers. Take yourself back. Why is it that when we’re thrown into situations that are new to us, our well-being is always the first thing we think of? Will to survive, I hear Darwin call out. That’s right. But when did the frontiers of the will to survive rise to king-size beds and green smoothies?

“Why is it that when we’re thrown into situations that are new to us, the first thing we always think about is our well-being?”

I get annoyed when there are no vegetables and no fruit at camp, my inner hypochondriac gets scurvy, I eat half the side lemon of lentil soup to keep from dying of vitamin C deficiency. I do this while stacking hundreds of cartons of ultra-high temperature milk. Did the tent city kids ever eat an apple? Smelled the muddy sweetness of a banana and sucked out a tomato? Complained about the texture of broccoli and the bitter taste of spinach? Tears well up in my eyes as I sort sanitary napkins by size, here, in our little supermarket where the people the things are for can’t even shop for themselves. We are used to an uncountable amount of availability. Of everything. I’m just becoming very aware of what a privilege this is. Our supermarket has no wheels and, with luck, comes once a month. Our supermarket is only closed on Sundays.

Today is Friday. The last few days have been so exhausting and nerve-wracking, so productive and emotional, that I’m as physically and mentally exhausted as if I’d run a marathon writing my dissertation. The mood in the village is tense. Almost all the volunteers are sick, we infect each other and have a hard time regenerating, in our containers. Yesterday the water pump broke. We have no more water. We can’t flush, we can’t shower, we can’t flush the toilet, we don’t have water to cook. We are dirty and tell Neanderthal jokes. After less than 24 waterless hours. What are people doing in the camps? Water is a resource, not something to be taken for granted. I’m angry at all the people who wash their cars, while I think of the children whose little bodies have never felt water. And it’s still hard for me not to compare the worlds I live in right now.

Wednesday. “50 more,” Nina calls out as we hand her the grocery bags. Our van is full. Maybe we should go with two cars. We take 250 food bags and 200 hygiene bags. Hopefully that’s enough for everyone, I think with each bag I pack into the car. All of them. Who do I mean by that? People in the camps that we reach out to? And what about the camps we can’t reach because we don’t know they exist? And what about the people who didn’t have enough money or enough strength to escape? Who are still in Syria and Lebanon and elsewhere. ‘All’ is a very elastic term. Yesterday we discussed whether each family (that we could reach) should get one, or two bags. Do we want to provide one family for three weeks, or two families for 10 days? Justice ends with the number of children – a family with seven children needs more noodles than a family with four. Can we compensate for malnutrition in pregnant women? And what about food intolerances? “Escape doesn’t know lactose intolerance,” says Franzi. The bags are stowed, we decide to go for the ’10 days all families variant’ so as not to start any internal camp fights.

“Escape knows no lactose intolerance.”

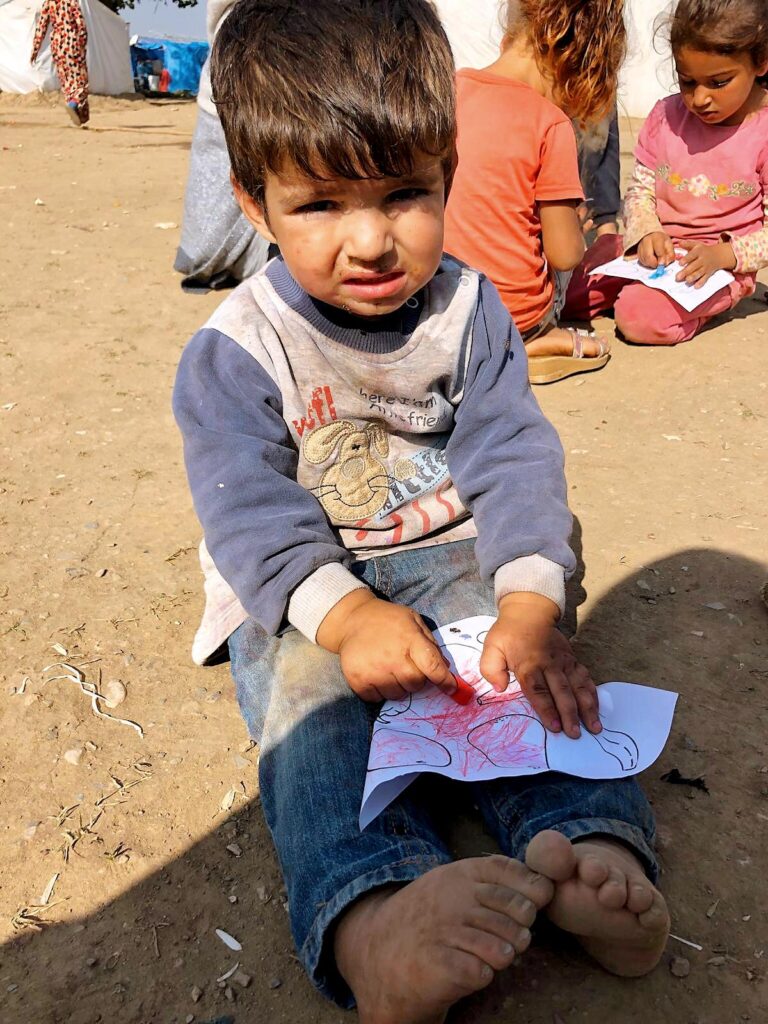

Today we plan to feed four camps. Ali asks if Nina and I can take care of the kids while the bags are distributed to the parents. I think about the restless chaos and my overwork from last time. We nod, knowing now what to expect. We learn Turkish children’s songs, in the evening in our container, think up a sports program, print pictures of fruits and vegetables, look for wax crayons. Today we are more prepared. I can concentrate better this time on the landscape passing us by. Izmir is huge, shining, one of the biggest cities in Turkey, hotel adjoining hotel, sea view köfte and promenade walks. We drive past the city, junkyards replace vacation resorts. It’s not pretty here anymore, the dogs on the side of the road, looking more like wolves, scare me. The camps are all different: one we find in the shelter of all olive groves, one on an old tomato plantation, another in the shelter of a field of ruined buildings. As different as the camps may look at first glance, they are all differently alike. As soon as people hear the sound of our van’s engine, they stream out of their tents. I’m surprised we’re not greeted cheerfully. There’s no waving or laughing, most of the children are crying, women are hiding behind their babies, hugging them to their chests, snuggling with their fathers, standing in front of their wives. The older children are braver, smiling when they see us smile. The children mirror us. As a boy gently strokes my arm, I press his small body against me, his mop of hair touching my T-shirt, the tips of my hair, my heart.

Out of the corner of my eye, I see Ali handing out the bags. There are only 20 families in the first camp – though every time I wonder where all the kids come from. People line up, thanking each other for the bags, relaxed laughter from everywhere. I’m more confident this time, I take the kids by the hand, we stand in a circle, bare feet, dirty earth and all, so many kids. We sing songs and make big movements while doing it. The children imitate us, the smallest ones sit between us on the floor, we shout more than we sing so that everyone can hear us, but it works. Nina hands out the coloring pictures, “Habla”, the girls and boys say, “big sister”, and grab the paper with their little hands. They color so calmly and with concentration, as if the most important thing in the world is to color this banana at this moment. “Elma,” I say, pointing to the apple. A girl in, brown tutu stained by mud, answers in Arabic. “Apple,” I say. We both laugh and I want to stay here forever, on the stone floor among tarps and ruins and old chicken coops. I feel comfortable here because I feel needed. And because the children’s laughter touches me so much that my whole body shakes. When did we forget to be happy about coloring pictures, even though our whole life is a giant mandala?

“I feel comfortable here because I feel needed.”

“Stop,” I yell, forgetting that no one here understands German. Sitting among hundreds of children in the dirt, I hear a babble of voices and can make out a discussion from the corner of my eye. I try to keep the children together, I can’t. There are children everywhere. We are in the camp where we distributed diapers last week. I recognize little Mohammed, children’s faces look familiar, I feel an instant connection, ‘I missed you’ I want to say, ‘I’m glad you’re still here’ I think. I hear Rashid speaking in Arabic, strained and determined. I hear some men shouting. I’m unfocused because I’m trying to understand the situation, there is a little boy, first the paper and then the wax crayon in his mouth. He swallows faster than I can look, I panic, try to pick the green crumbs out of his mouth, grab him under the tongue, he gags and spits, he spits out the wax crayon remnants and I shake him because I was so afraid I had poisoned him. The little boy, barefoot and without pants. I hug him to me. “Please don’t eat any more crayons, okay? Ever, okay?” We cuddle, and I stroke his malnutrition-trained fat child’s belly and close my eyes for a small moment. Hope he gets a whole lot of the noodles and rice and bulger we packed. I’d love to hide all the Hipp jars in the world in his parents’ tent, I can’t. And then a lot of things happen at the same time. “We have to go,” says Cam, approaching our tangle of children. „Now“. I sense it’s a now and not a ‘right now’. „Everything okay?“ “Everything okay?” We collect the pens, I deliberately overlook some pens because it makes me so sad that kids don’t even have pens to practice writing their names. “Now,” Cam says again, and we jump into the van without even getting to say goodbye to the kids. Rashid is missing. „What happened?“ I look out the window, see men gesticulating wildly, hear children shrieking. More families than grocery bags, Cam says. We can’t control if people double up, if some greedy get more and others get nothing. Hunger and worry are a bad mix. Did all families get a bag? No one answers me. So they didn’t? No one answers me. I hate that, I say, and everyone nods.

“Hunger and worry are a bad mix.”

It’s late when we get home. I’m so tired, from bagging and distributing bags and bagging and distributing bags. Before we can eat anything, we have to pack the van for the next day. 200 grocery bags, 200 hygiene bags, plus diapers. One bag weighs almost eight kilos. Yasmine and Mutea carry a bag together, one bag at a time. I know the young family on the Syrian border also lived in a tent camp. Rashid accompanies us on each food tour, translating and explaining, Sheia helps cook, Mutea and Yasmine pack the car. I wonder if the girls realize they are packing bags for children who were not as fortunate as themselves. I stroke Mutea’s head, she looks cute in her new dungarees, a donation. I’m starting to bond with the family. Sheia took off her headscarf a few days ago when I was in the room. Her English is getting better, in the evenings she plays cards with us from time to time, she starts talking about herself. Sheia is the same age as me. Her eldest daughter is 10, I’m 23, and sometimes I have trouble taking responsibility for myself. Sheia fled Syria with three children while I had the opportunity to study. Mutea sits on my lap, I sit on the floor, it’s cold, there are still hundreds of kilos of flour waiting to be packed in the warehouse. We’re too exhausted to talk. Tomorrow is a new day. Tomorrow we need to buy rubber boots.

“Can you concentrate at all?” Franzi sits cross-legged on the carpet in front of me and looks at me. “I’m fine,” I say. Yasmine and Mutea shriek with joy, the other volunteers shriek too, we play cards, they play cards, it smells like börek. In the evening we have to sit inside now, it’s too cold outside. Today is Friday. We have 1000 rubber boots sorted by size, shoe size 17 is so insanely small. Ali and Josh and Cam bought a wheelchair, one of the camps has a disabled child. Our van is broken. We don’t know if we’ll be able to hand out bags and shoes tomorrow. “We’ll see,” Ali says, shrugging his shoulders as his eye twitches. Ali is exhaustion personified. Yasmine is laughing, Yusuf is sleeping on the sofa we are all sitting in front of, a baby cat is lying on the blanket on top of him. We still have no water. Still, there’s no place in the world I’d rather be.

About the author:

Christina Lopinski was a volunteer for STELP in the IMECE village in Cesme/Turkey from October to December 2019. The 24-year-old has lived in Berlin for a long time and during that time wrote for the Berliner Abendblatt, the B.Z. and the Wiesbadener Kurier. She currently works for the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung.